Early help is the best option for children and families. We need to protect it

Our new research finds that local authorities need more support to expand vital early help services and turn the tide against late intervention

Today we launch a new report, “Too Little, Too Late” which looks at the number of children in England who get early help, for the first time.

‘Early help’ is the name for services that support children and families before they meet the threshold for intervention from children’s social care. These services might include parenting support, play and activity groups, or more intensive services like counselling and disability support.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of families of the UK access early help support in some form or another. Accessing early help services can prevent children from coming to harm and needing to go into care. Because of this, it can also save local authorities money.

In other words, early help is a critical public service.

However, funding cuts to local authorities and the rising cost of social care have squeezed budgets for preventative services like early help. Because early help is not a statutory service, there is no national data on how this has affected the number of children offered help.

To fill these gaps, we asked local authorities in England to provide data on how many children received support from early help services in the five financial years from 2015-16 to 2019-20. This is what we learned:

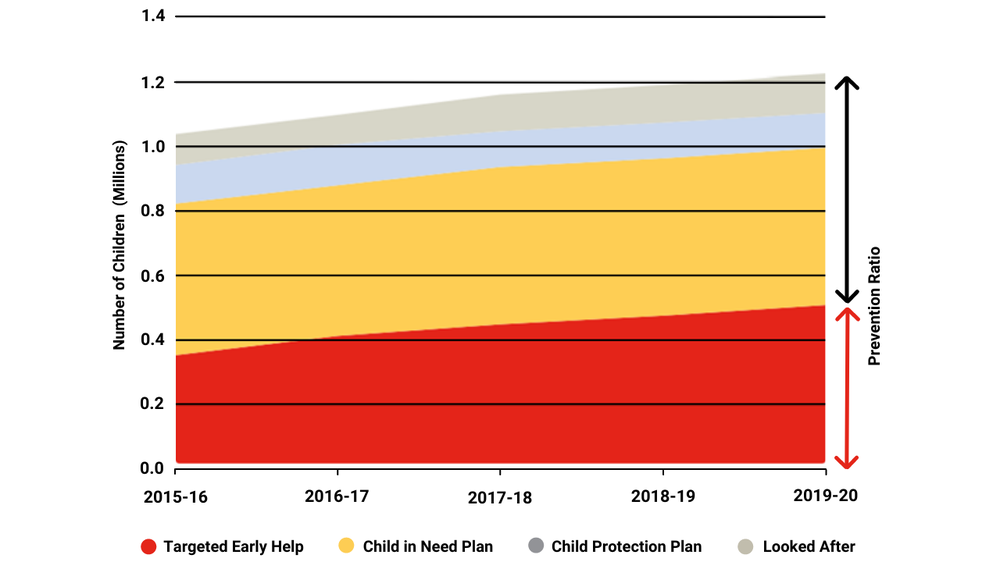

For every two children receiving early help, there are three children receiving more costly and intensive social care services. We call this the ‘prevention ratio’. In a well-functioning social care system, more children should receive preventative support than need costly social care services and crisis interventions.

Figure: Components of the Prevention Ratio. Number of children receiving targeted early help and social care interventions in England at any point in the year, 2015-16 to 2019-20.

Overall, early help provision rose across the years that we looked at. In 2015-16, 3.1% of children in England got early help support, compared to 4.3% in 2019-20.

The local authorities that responded to our request reported providing targeted early help to anywhere between 0.6% and 15.4% of children.

Children in different parts of England have different needs, so you would expect to see some variation between local authorities. However, the differences we find in the data are not well explained by underlying differences in child poverty or the number of children entering social care.

This implies that what really matters for early help is how much the local authority can prioritise these services in the face of a difficult financial situation.

When children are referred to social care teams for an assessment, and do not meet the threshold for social care support, social workers have the option to close the assessment and make a ‘step down’ referral to early help.

From our data covering 2015-16 to 2019-20, we estimate there were 1.26 million occasions where a closed assessment did not lead to an early help referral. In 25% of these cases, the child in question was referred back to social care within 12 months, suggesting early help support might have helped them in the interim. This adds up to approximately 64,000 children per year.

Squeezed by funding cuts and rising costs of social care, nine out 10 local authorities cut spending on preventative ‘early intervention’ services like early help and children’s centres between 2015-16 and 2019-20.

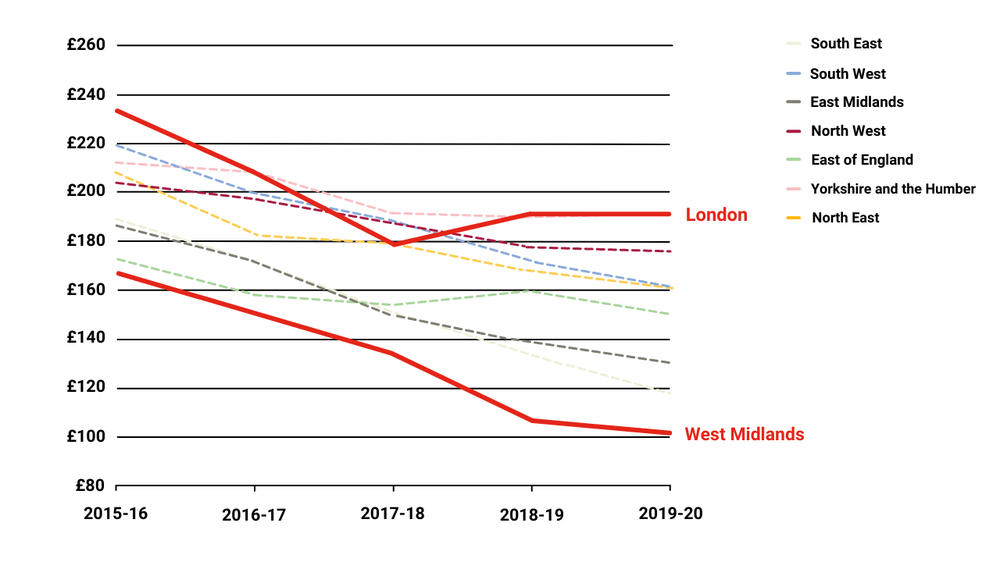

Eight of the 10 highest spending local authorities in 2019-20 were in London. Over the five years we studied, the early intervention spending gap between London and the West Midlands grew to £90 per child.

Figure: Per-child early intervention spend across English regions between 2015-16 and 2019-20 (2020 prices)

With the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care due to report later this Spring, we have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to secure a future for early help. We can stop the slide towards late intervention in its tracks.

Local authorities currently have no clear legal responsibility to provide early help. This means that services like early help are the easiest to cut when they come to make difficult financial choices.

A legal duty on local authorities to provide early help is needed to protect vital services from cuts and raise minimum standards of provision.

Local authorities want to improve early help provision but feel unable to without proper resourcing. Government should commit to restoring funding for early intervention services like early help.

An increase of £1.93 billion above 2019-20 spend levels is needed to match the per child spend on early intervention services in 2010-11. The costly and harmful cycle of crisis response will continue without adequate support for early intervention.

To improve early help, we need to know what is happening and what works. Government should require local authorities to report on how much early help they provide and what services families receive.

To bring clarity to the wider children’s sector, the Department for Education should publish a national outcomes framework for children’s services to guide programme design and evaluation.

Looking for research to inform your work or drive change?